By Neha Kirpal

Historian Ira Mukhoty’s first book Heroines: Powerful Indian Women of Myth and History (Aleph, 2017) consisted of tales of mythical heroines including Draupadi, Radha and “six real women who played extraordinary roles but who weren’t written into textbooks”. Her second, Daughters of the Sun: Empresses, Queens and Begums of the Mughal Empire (Aleph, 2018) was about the disappeared women of the great Mughals.

In her newest work, Akbar: The Great Mughal (Aleph, 2020), she moves away from a female-centric theme but does highlight the role of women in the making of the emperor.

Ira Mukhoty.

Ira Mukhoty.

The Delhi-based author, who studied in Delhi and Cambridge, talks to us about untold tales of mythical heroines and Mughal queens, and their relevance in contemporary times.

Which were your favourite stories from your first book, Heroines?

Some of the little known facts about women I discovered while writing Heroines were facts that were uncomfortable within the conservative narrative they were usually framed in, and so were gradually erased and forgotten.

Rani Laxmibai is deified for dying a warrior’s death but it is forgotten that she would have preferred to live, and rule her kingdom of Jhansi, and that she conducted a long, determined diplomatic correspondence with the British.

As for the 16th century Bhakti saint Meerabai, the claims and counterclaims are endless – that she was an elderly widow, tending to her husband till the end of his life before leaving home almost as an act of renunciation – whereas her songs point rather to the fact that she escaped an oppressive, traditional household, leaving behind her husband and in-laws as a young woman, in response to a divine call.

I find it fascinating that Hazrat Mahal was a courtesan of dubious pedigree, possibly with part African heritage, and that Wajad Ali Shah divorced her and repudiated his son with her. Nonetheless, when the events of 1857 broke out, she found the courage, confidence and acumen to rise to the occasion.

What inspired the second book, Daughters of the Sun?

One of the ‘heroines’ I wrote about in my first book was Jahanara Begum, daughter of Mumtaz Mahal, who became one of the most wealthy and powerful women of her time. She wrote a biography in which she challenged Sufi masters’ dictum that, as a woman, she could not claim the same spiritual status as a man. She not only patronised extensive building works in Shahjahanabad (Old Delhi) but is buried in Nizamuddin Auliya’s Dargah, showing her Sufi leanings. And yet I had never come across these astounding facts, pointing to a systematic erasure of the voices of these women. Then, I was lucky enough to stumble on the academic work of feminist historian Ruby Lal, who has analysed the harem of the early Mughal emperors, and I was introduced to a whole new way of imagining the Mughal harem.

When did you develop your fascination for royal queens in Indian history?

I forayed into writing to find out more about iconic Indian women who could be captivating and believable role models for young women. My two daughters were young at that time, so this was a personal quest. I was not necessarily looking for only queens but historical recordings, scant as they are for women, are almost non-existent where non-royal or non-elite women are concerned and so in the end, my search did include more queens and begums.

I used the stories of mythological characters as well as historical women, because in India we have a peculiar reality in that mythological women are revered as real persons, while historical characters are easily forgotten and the narrative of their lives manipulated and altered. So, to understand this process better, I tried to understand how Draupadi and Radha, popular pan-Indian figures, had evolved over the centuries. And it became clear that they were also subjected to a form of censorship over time, their idiosyncrasies and transgressively assertive challenges morphed into a much more acceptable vision of Indian womanhood.

Like their historical sisters, Draupadi and Radha posed far more troubling challenges to authority in the earlier recordings of their stories; Draupadi questioned her husbands’ ‘maryada’, or manhood, for example, and Radha was first portrayed as ‘paraya’, a married woman who belongs to another and yet escapes the confines of acceptable society to meet Krishna.

The historical Queens and Begums similarly have much more vaulting ambitions for themselves than what is remembered. They want to rule, in the place of brothers and adopted sons, they want to follow their desires and their heart and, most movingly, they want to be remembered.

What can today’s leaders, both in the corporate world and electoral politics, learn from these Indian queens?

Aside from the specific examples in Heroines, who demonstrate that women have all the skills required for leadership with compassion, I would propose that the great need of the hour is to encourage women to participate in all aspects of public and social life. That it is only by creating environments that foster the participation of women in large numbers that the endemic injustices of a society skewed against women can be addressed.

Did women in Akbar’s court play any important part in the cultural heritage that Akbar is best known for?

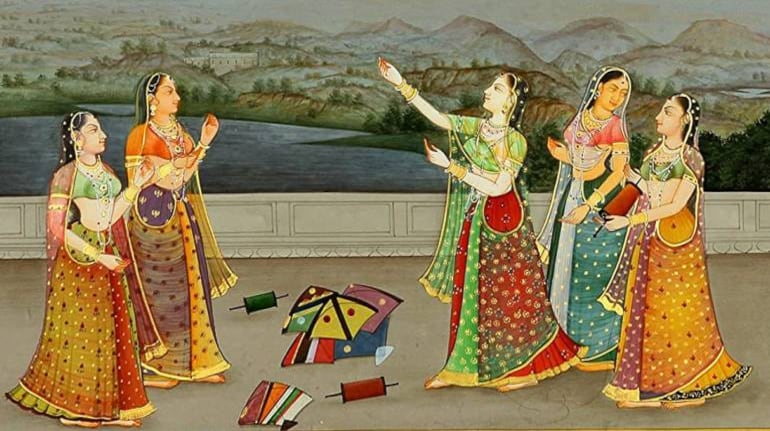

Women were very much part of Akbar’s effervescent cultural experimentation. Akbar’s first major dispute with his milk brother Adham Koka occurred over Adham Khan’s appropriation of treasured dancing girls from Baz Bahadur’s court. These women were highly coveted by Padshah and courtiers alike because it was well known that Mandu was a great cultural centre and these dancing girls would add to the lustre of the Mughal court. There were women among the miniature artists and at least three women artists were listed among Abu’l Fazl’s list of Mughal maestros and that leads us to wonder how many more there may have been.

The miniature paintings of the time are a valuable primary source of information, and from them, it is clear that there were women musicians as well. The elite women, meanwhile, were patrons of art. Hamida Banu Begum, Akbar’s mother, owned her own copy of the Persian Ramayana, and asked to view it one last time before her death. Akbar’s Rajput wives, including Harkha Bai, brought their language, their food and their music to the zenana as well. So women were involved in all aspects of Mughal culture, it is just that the record-keeping for their influence is much more arbitrary.

Did women in Akbar's court play an important part in his Sufi beliefs (Din-i Ilahi)? Can the present generation learn from this?

Hamida Banu Begum was a direct descendant of the great Sufi saint Ahmad-e Jam, known as the Colossal Elephant. If we look carefully at the symbolism that Humayun and Akbar used, it is clear that this connection was extremely valuable to the Mughals. Monarchs had long used a connection to a Sufi lineage to bolster their claims and for the Mughals, this initially came through the maternal line, through Hamida Banu.

Later, Akbar became very fond of the Chishti saints. When a son was born to Akbar, he incorporated the entire family of Shaikh Salim, the Chishti Sufi – his sons and their wives, to become tutors and milk-mothers to his children. When Akbar married Rajput women, especially Harkha Bai of Amer, this brought in a great deal of Rajput Hindu influence, since these women were allowed to retain their religion and carry on performing all the rites associated with it.

Later, Akbar became very fond of the Chishti saints. When a son was born to Akbar, he incorporated the entire family of Shaikh Salim, the Chishti Sufi – his sons and their wives, to become tutors and milk-mothers to his children. When Akbar married Rajput women, especially Harkha Bai of Amer, this brought in a great deal of Rajput Hindu influence, since these women were allowed to retain their religion and carry on performing all the rites associated with it.

The change in Akbar himself was perceptible from this time on, through the abolition of pilgrimage tax for Hindu sacred places and the abolition of slavery affecting women and children. Then as time went on, Akbar actively sought out great thinkers among the Sufis, the Jains, the Zoroastrians, the Brahmins, Christians, Hindu ascetics, Mahdavis and others. This indisputably led to a cosmopolitan court, with the eventual elaboration of Akbar’s Sulh-e kul philosophy, of an active, empathetic toleration of each religion.

If there is a single lesson that I would emphasize for today, it would be that we study this spirit of Sulh-e Kul. Of this fostering of a spirit of mutual understanding and emapthy. Of removing ignorance and falsehoods when judging our neighbours, and encouraging an element of compassion in our dealings with followers of all religions.

Despite several women scaling heights in political power and assuming important roles in statecraft, their contribution has not been duly recognised and they are seen only as contributing partners to kings. Do you think books like yours are changing this skewed narrative?

I certainly hope they are. There is a huge misperception that needs to be corrected in this regard. In her book Invisible Women, Caroline Creado Perez examines the construction of the world – its gadgets, tools and parts – and argues that these are designed almost exclusively for men because of data bias which excludes women from the reckoning.

The standard human experience has almost always been accepted to be a male one, and so a great deal of our experience, from our language to our histories, has favoured male narratives. Recorded histories almost completely ignore women’s voices, and I think there is a growing realisation that a fundamental correction is required.

Indeed there needs to be a seismic re-evaluation of the lenses through which we evaluate things like history, to start taking into greater account the importance of art, language, etiquette, nurture, care and food, which have often been areas deemed less important, and are the ones women are a great deal more influential in.

Discover the latest business news, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!